‘I was led out of the station into a world of Christmas trees. In front of most of the houses stood a tree lit by electric light, and in the middle of one wide street was a huge one, a pyramid of solemn radiance. I felt as if I had walked into a Christmas card, – glittering snow, steep-roofed old houses, & the complete windlessness, too, of a Christmas card. Not since since 1909 had I had a German Christmas, the last of a string of them, & seeing that 1909 is a long while ago, and that many things have happened since, it was odd how much at home I felt, how familiar everything seemed & how easily this might have been the Christmas, following in its due order, of 1910.’

Much, indeed, has happened since Elizabeth had last spent a German Christmas when she goes to visit her daughter Beatrix von Hirschberg, her grown up June Baby of the Elizabeth diaries, in the Bavarian village of Murnau in 1937. Athough the wonderland of a German winter village decorated for Christmas may still work its magic, Elizabeth has arrived in Nazi Germany and even the snow cannot conceal the changes that have taken place since 1909 as Elizabeth will soon discover.

But for now all is well. Elizabeth is ushered into the house full of the enchanting, well familiar smells of ‘Lebkuchen, Leberwurst, red cabbage, roasting goose and the more serious smell, serious because it also attends funerals & envelopes mausoleums, of the fir tree standing ready to be lit in the drawing room’. As the family, the servants and the family dogs gather around the Christmas tree in the drawing room, Elizabeth revels in memories of Christmas at Nassenheide:

‘I knew exactly what I would find inside the room, for had I not for years myself arranged such rooms with their tree & tables of presents? There were the tables in a familiar row, one for each person, piled with parcels tied up in gay paper & silver ribbon, decorated with pots of cyclamen & azaleas, & there was the tree with the little creche at its feet, & marzipan sheep flocking round chocolate Wise men’.

But as the household stands in adoration of the tree, the festive spirit is upset by the two family dogs ravaging the nativity scene: ‘while we were busy singing Stille Nacht [Silent Night] to the accompanying gramophone, the Scotties, who had no manners, before our outraged eyes ate, one after the other, all the marzipan sheep. Because of custom we couldn’t do anything but stand stiff & sing. Both tradition & decency rooted us in immobility’.

While little Jesus is saved in the nick of time once the record has finished, Elizabeth muses that ‘only Germans could be as disciplined as this, & able by training to appear absorbed in holy words while their hearts must be boiling within them’. And although the dogs are banished from the gathering, Elizabeth is feeling a little ‘subdued’ as she ‘‘could have sworn they laughed as they were led away’ because ‘inside them, safely tucked away, were the sheep‘. Luckily, the festive mood soon returns as the family open their presents with ‘cries of excitement’.

Although the incident is undoubtedly funny, Elizabeth feels ‘this was the second time I had been subdued’ that evening. For when her daughter met her at the station, confused by the familiar garb of Lederhosen, Elizabeth had mistaken the taxi driver for her son in law to the amusement of her daughter. All is not as it seems in Germany, but Elizabeth finds it still hard to believe. Feeling a little full and sleepy after the Christmas dinner of goose and wine and Baumkuchen, she remarks,

“‘It’s impossible […] to imagine this Germany is any different from the Germany I knew’.

‘Oh, but it is –‘ began my daughter, instantly to be stopped by her husband with a quick ‘Take care-‘ for one of the maids had come into the room. This woke me up completely. Take care? What of? Slightly subdued, for the third time, I allowed myself to be put into my fur coat & driven to midnight mass.’

The service, Elizabeth finds, is as festive as ever: the church is lit up and ‘streams of dark figures – streams, I noted with astonishment – piously silent, were flowing up towards it’, singing once again Silent Night, Holy Night. As an avid reader of the Times and knowing ‘what [was] happening to the churches of Germany’, Elizabeth cannot ‘believe her eyes’ and opens her mouth to enquire:

“’But –‘ I began, as I hung on to my son-in-law’s arm.

‘Take care,’ he quickly whispered, gripping my hand.

Take care. Again. Must one then for ever take so much care? And, after all, what had I said except But?’

***

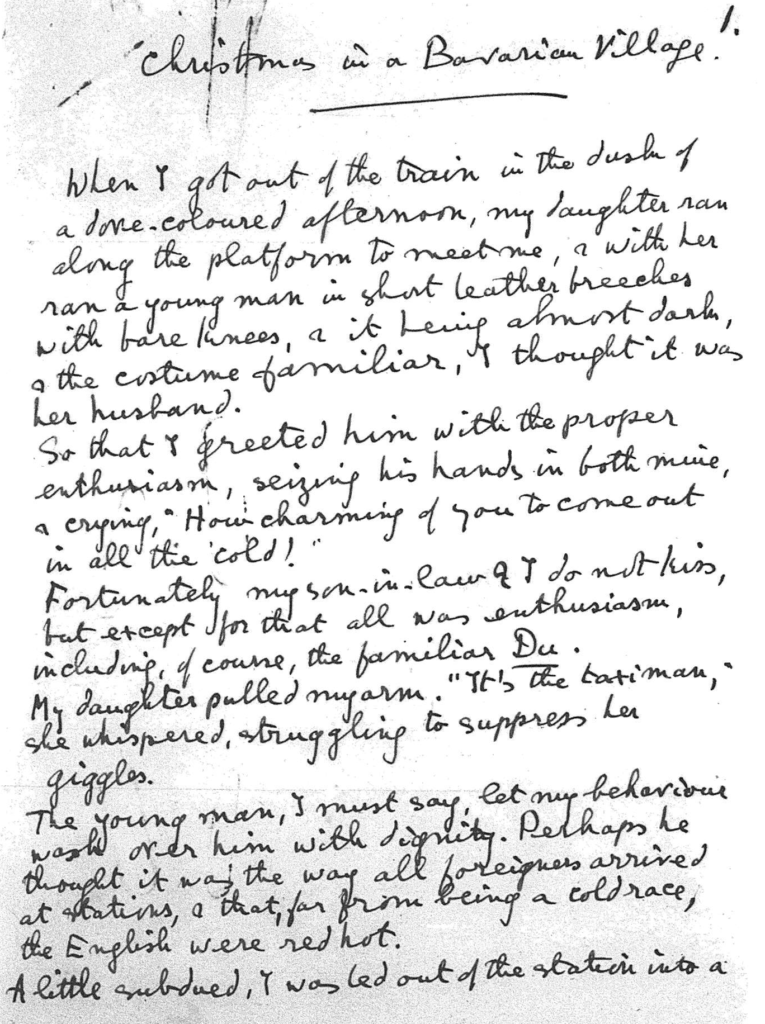

Von Arnim’s Christmas tale ends on a question, a contradiction even – a dangerous thing in Nazi Germany where silence has become the safest, or indeed, the only option to navigate life in a Fatherland that has transformed from Weimar Republic into the Third Reich in the space of just a few years. The short sketch captures the mood of a country in the grip of terror – Silent Night has become the unofficial anthem of the German nation. ‘Christmas in a Bavarian Village’ is a brilliant piece of political satire that deftly elucidates the nexus of politics and worship, censorship and national character, brutality and passivity in the name of Kultur. Although it was intended for publication in the Times, unfortunately it did not reach England in time for publication. The manuscript is now at the Huntington Library together with most of von Arnim’s papers.

As Elizabeth, von Arnim adopts her familiar stance of the naïve traveller to offer a clear-sighted political analysis of Hitler Germany. As always, she uses absurdist humour to lay bare the iniquities of her subject. The light-hearted incident of confusion at the train station, which apparently really happened and was worked into the sketch, is transformed into an ill omen. Visitors had better not be lured in by the familiar dress of Lederhosen: those who wear it have become unfamiliar. Family members may have turned into strangers upon closer inspection. Von Arnim draws the portrait of a nation who, immobilised by a deeply ingrained sense of discipline in the name of custom and Kultur will let a bunch of dogs violate the Christian values of love, compassion and innocence in the name of civilisation and watch on as their brethren are one by one led to slaughter like sheep. The justice meted out to those smug little Nazi terriers is ineffective: the damage is done, and the dogs are laughing.

Von Arnim points here at the key question that remains troubling to this day: How could let Germans let the atrocities of political and racist persecution happen right under their noses and in broad daylight? Why did no one speak up? One of the strengths of von Arnim’s writing is that, rather than showing us Nazi Germany from the perspective of a superior outsider, Elizabeth herself is ‘subdued’ into complicit silence. As readers we share her bewilderment, but we can also feel the fear as it reverberates through her daughter’s family and begins to take hold in Elizabeth herself. The reader might feel a little ‘subdued’ themselves by the end of the piece. Von Arnim’s Thankyou letter, written to Trix shortly after her departure, shows her regaining the power of speech, full of concern, but also relieved to be home again with her dogs:

‘Darling little sweet one

I hated seeing you fade away into the icy distance, & how I wish you could have jumped into the train & abandoned your duties & come off with me! […] I so loved the whole time with you, & my beautiful Christmas & as for the Tüte [gift bag] you gave me, it was full of lovely surprises, & after five hours of complete silence I began as usual to recover & took a real interest in the little parcels inside. But how glad I was to get into my bed & to see my darling Russells again!’

Von Arnim had been reluctant to travel to Germany. Earlier than many – not least, perhaps, because she spoke German and could listen to Hitler’s speeches in the original – she had recognised the dangers of the Nazi regime. Her clear-sighted political stance had caused tensions with Trix, who, influenced by German propaganda, had initially been positive about Hitler’s rise. However, as the new regime showed its colours ever more clearly, Trix and her husband, Anton von Hirschberg, a high-ranking officer, had grown critical and increasingly fearful of the new Nazi rulers. After Hitler’s invasion of the Sudetenland in 1938, a desperate Trix asked her mother for narcotics to commit suicide should things get worse. When they met again in Switzerland in November that year, Trix was scared to the point of paranoia and refused to talk openly even in the privacy of their Swiss hotel room. After their departure, von Arnim wrote to her daughter Liebet in the U.S.,

‘Little Trix breakfasted in my room, she very sad at parting, and how I hate her going back into those dangers. The sun came out and we walked once more along the lake walk.’

It was the last time that mother and daughter spent time together. Over the following years, their long-standing correspondence became increasingly domestic as Trix praised the Nazi regime loudly in her letters, and von Arnim restricted herself to family news, dog tales and comments on the weather with occasional snipes against ‘Aunt Kitty’, their codename for Hitler. And yet, in 1940, von Arnim, eternally optimistic, wrote to Trix’s daughter Sybilla in England about her thoughts for Germany’s future:

‘How thankful I am you have finished with Nazis for ever. Some day, when they have all been got rid of, & the other Germans reappear, Germans like Teppi [former governess of Trix and her sisters & long-standing family friend], of whom there are thousands & millions, we will be able to go there happily & enjoy what is so beautiful there.’

In her last surviving letter to Trix (written in German to appease the censors), she holds out hope as well:

‘Aunt Kitt, for example – how that conceited old woman goes on. Old maids like her usually have a bad tongue and one mustn’t believe all the nasty stories she tells. The doctors say she will never recover again and one has to be prepared that she might die in a few months.’

Although it would take a little longer for Hitler Gemany to collapse, the Hirschberg family all survived the war. Trix’s daughter Sybilla married an Englishman and, just in the nick of time, managed to leave Germany. Anton von Hirschberg retired from his command in 1940 and did not see action again. Trix was interned at a concentration camp for half a year towards the end of the war. She survived the ordeal and lived until 1987, passing away at the age of 92.

Sources

Elizabeth von Arnim, ‘Christmas in a Bavarian Village’ (Countess Russell Papers, Huntington Library, CA)

Letters by Elizabeth von Arnim to Beatrix (Trix) von Hirschberg, Elizabeth (Liebet) Butterworth and Sybilla Ritchie.

Joyce Morgan, The Countess from Kirribilli. The mysterious and free-spirited literary sensation who beguiled the world (Allen & Unwin, 2021)

Jennifer Walker, Elizabeth of the German Garden. A literary journey (Book Guild, 2013).

One thought on “Silent Night – Christmas in a Bavarian Village”

This was an amazing read–thank you Juliane. I have never read this unpublished sketch by von Arnim so it was great to get a sense of the original, as well as your superb commentary. The sketch is certainly not our traditional Christmas fare and one wonders what readers of the Times would have made of it, if it had been published! It’s pure von Arnim, isn’t it, in terms of its sophisticated political critique, delivered under the cover of warm domestic details and sparkling wit? Thanks again for highlighting this forgotten literary gem.